WWII Japanese Mass Incarceration collections

Haunting photos document a shameful chapter of America’s history—the forced displacement and incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII.

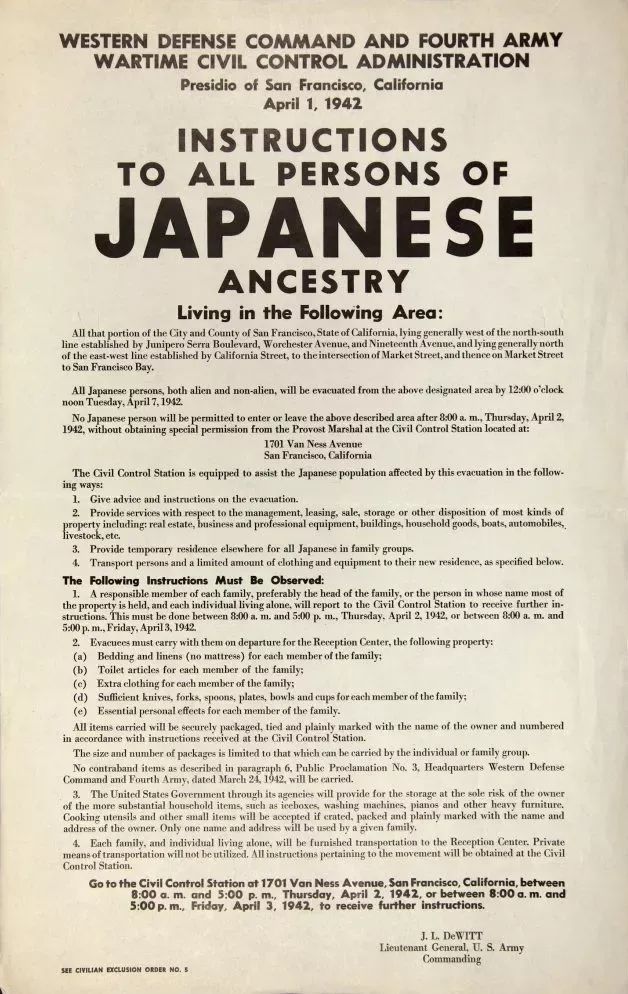

Two months after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, on February 19, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, authorizing the roundup and mass detention of Japanese Americans living on the west coast of the United States. The order granted the military broad authority to divide the western United States into military zones, from which “any or all persons may be excluded.”

While the order did not explicitly target any ethnic group, its clear intent was to incarcerate American citizens of Japanese descent in concentration camps on U.S. soil.

This shameful chapter in American history is extensively documented in the Library of Congress and the National Archives. With only 48 hours notice, more than 120,000 people were forcibly removed from their homes and sent to “internment camps”. The incarceration lasted for four and a half years.

Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange photographs

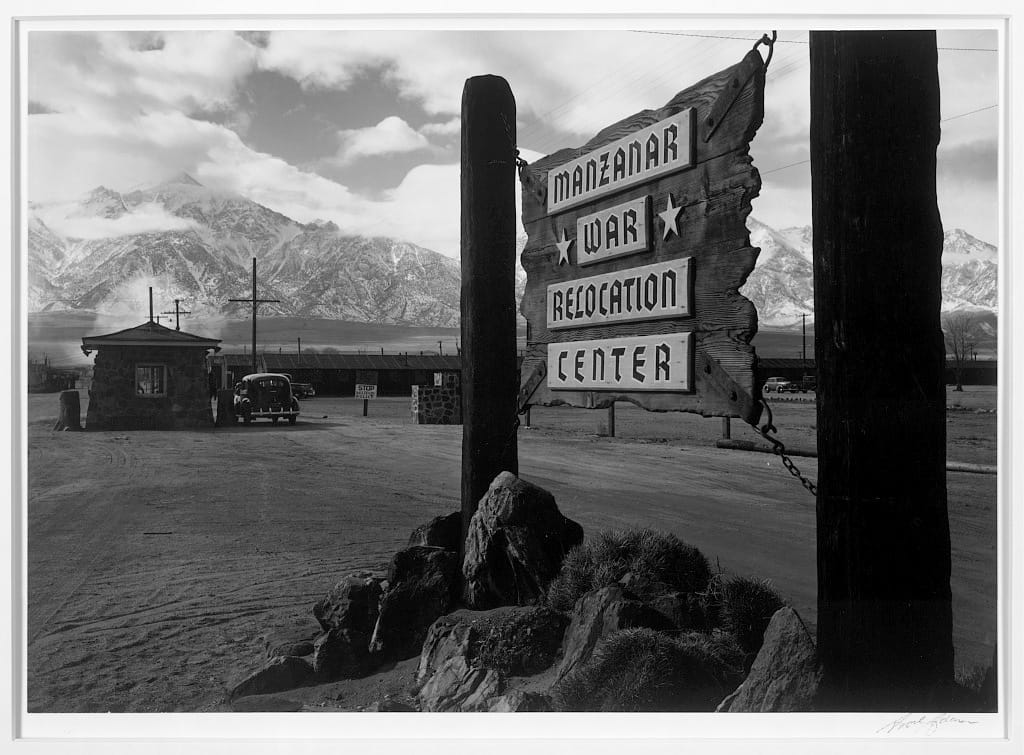

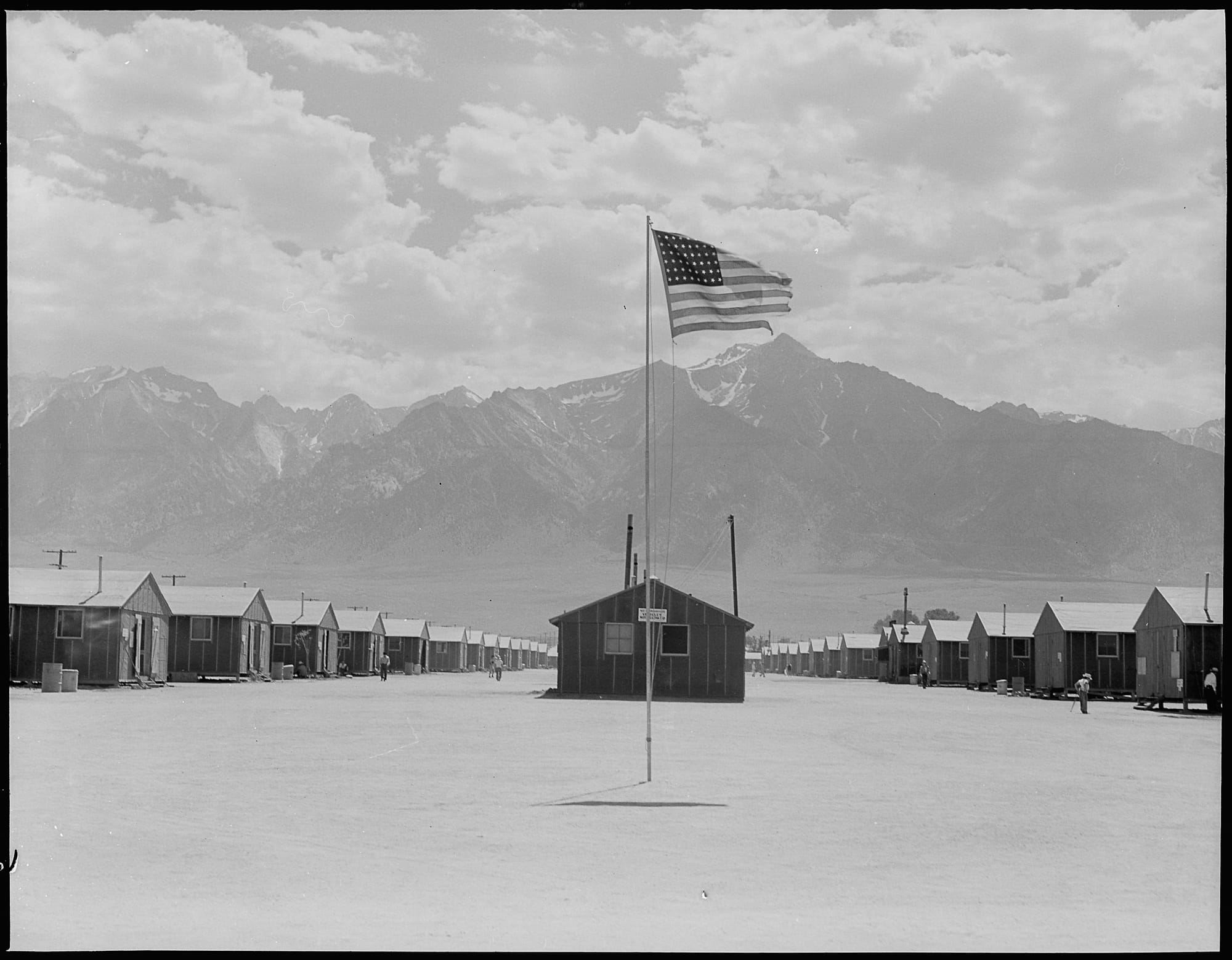

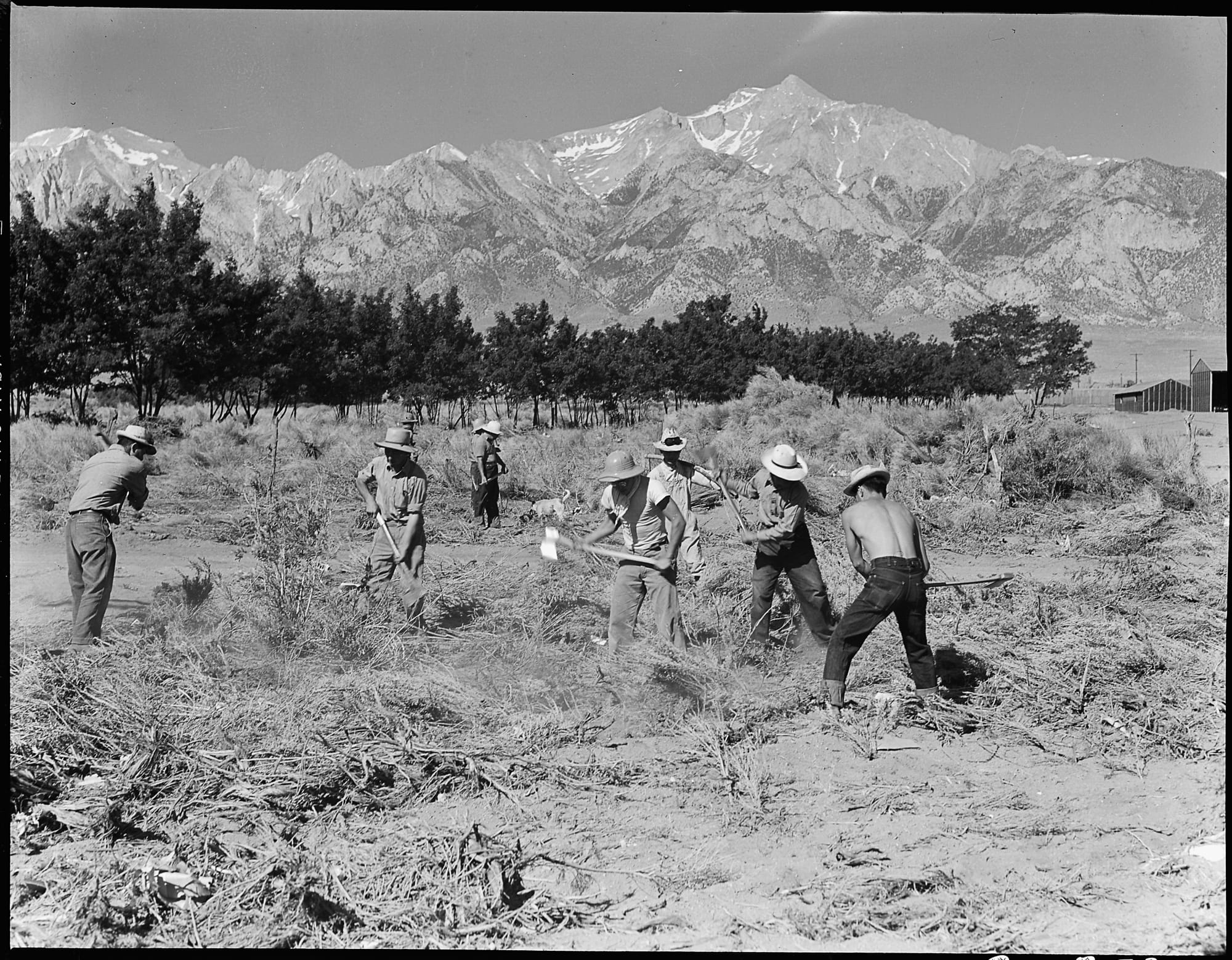

The first records I came across from this collection were the striking photographs taken by Ansel Adams in the fall of 1943. His images document life inside the Manzanar War Relocation Center, near Death Valley, CA — one of ten such detainment camps built in response to the executive order.

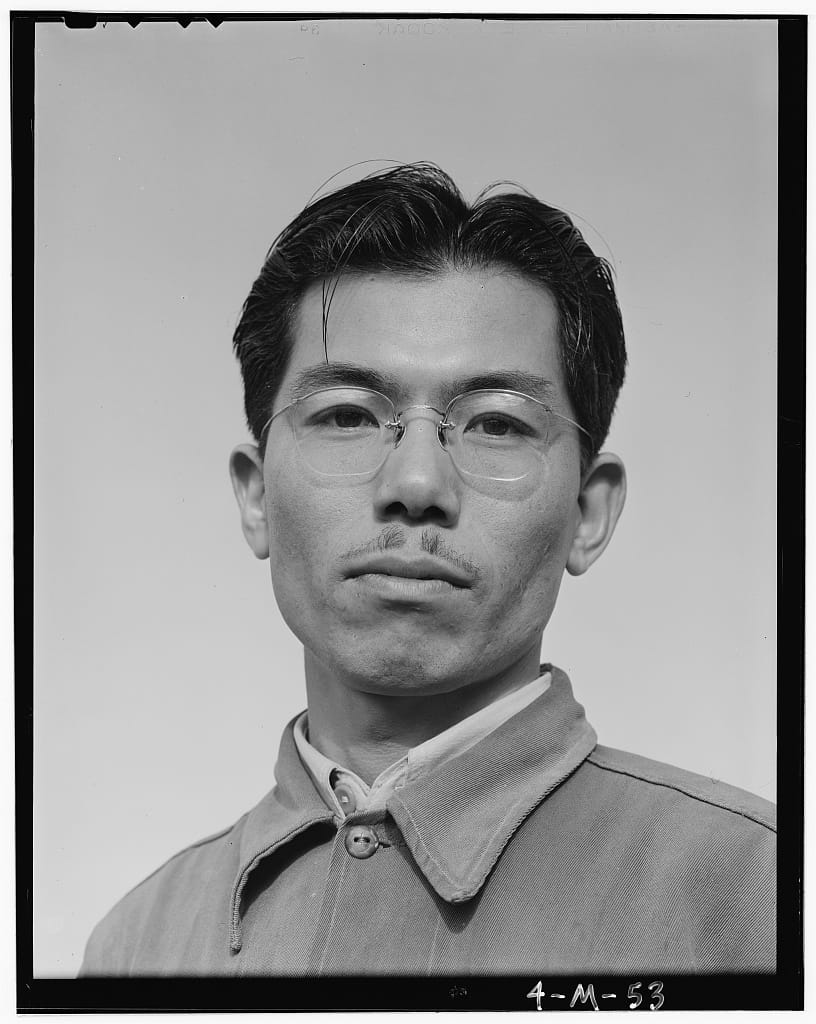

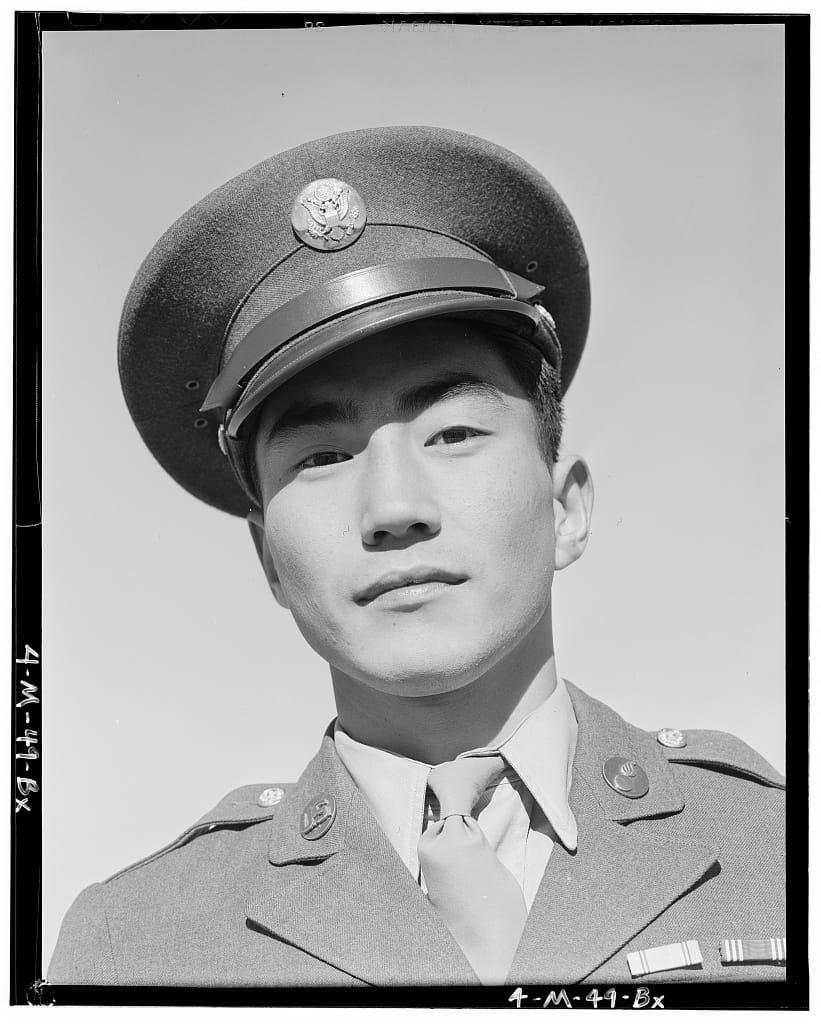

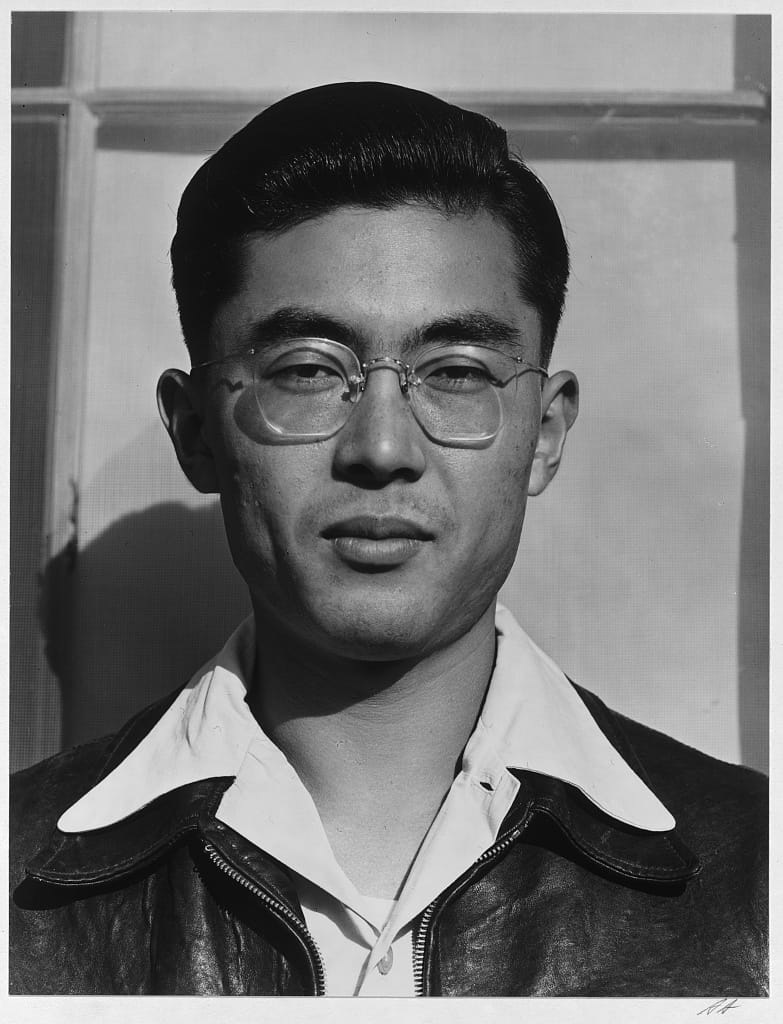

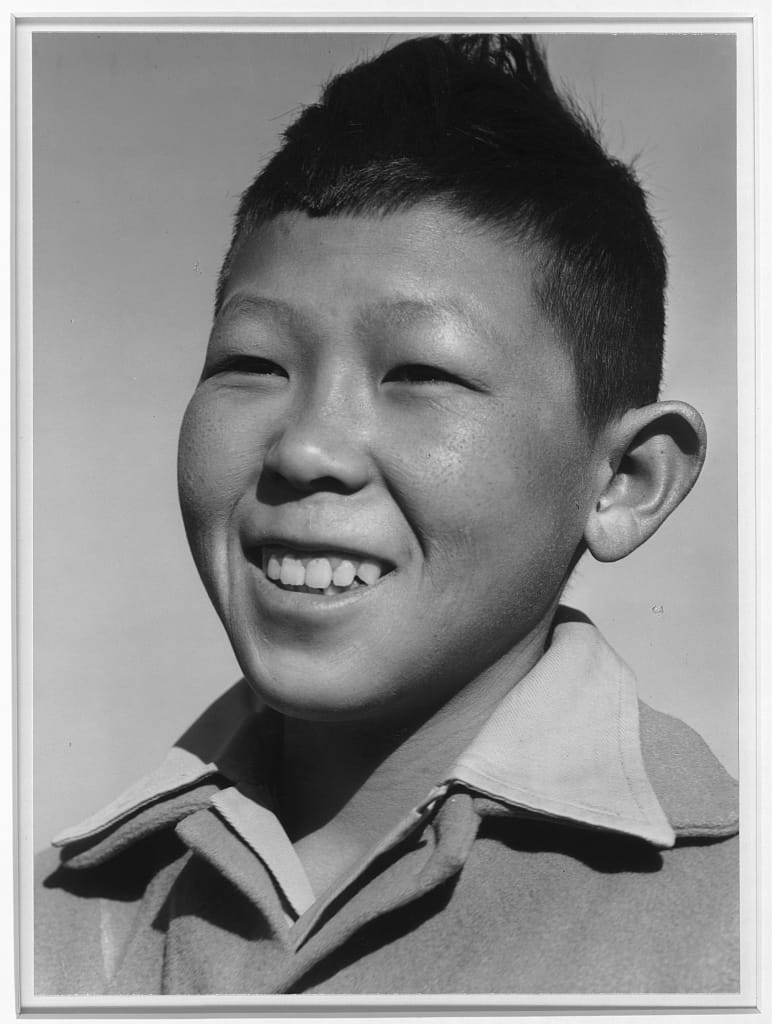

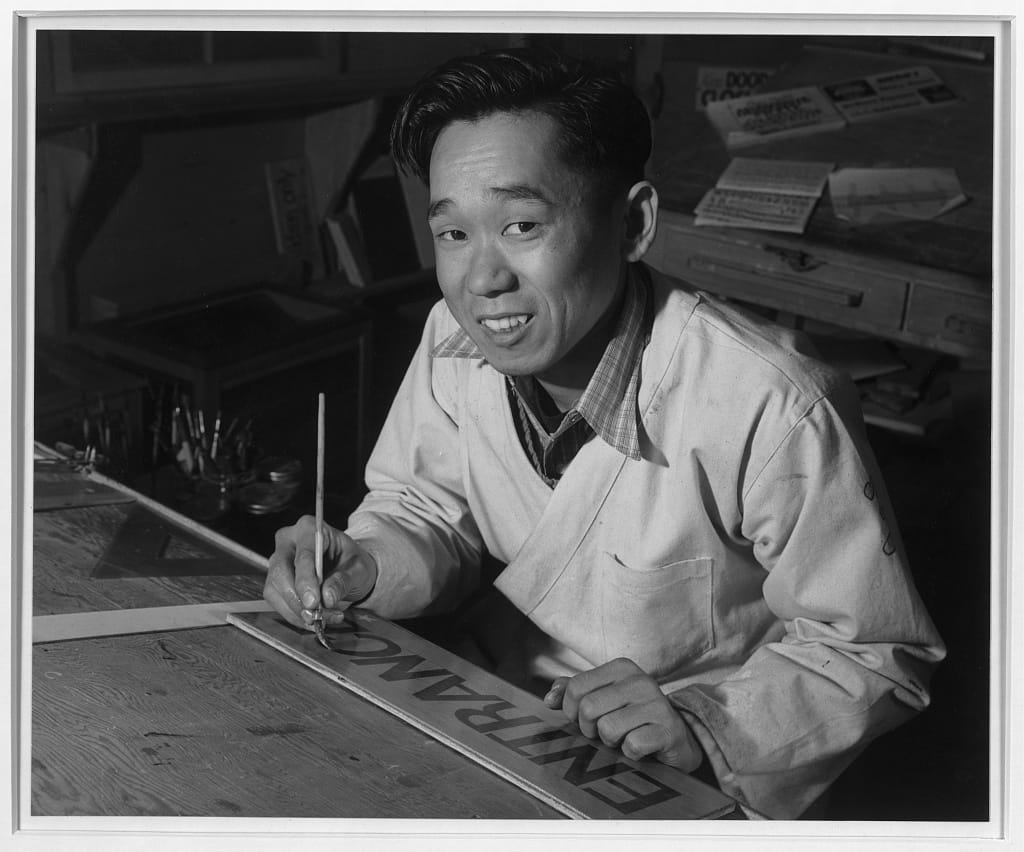

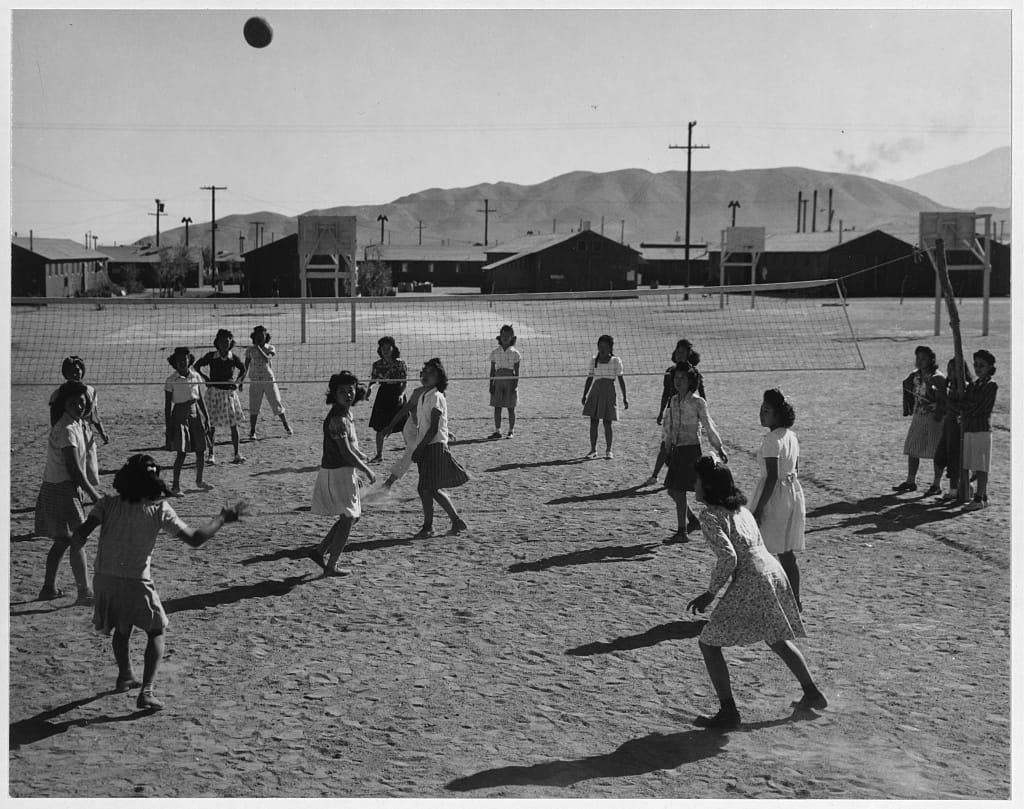

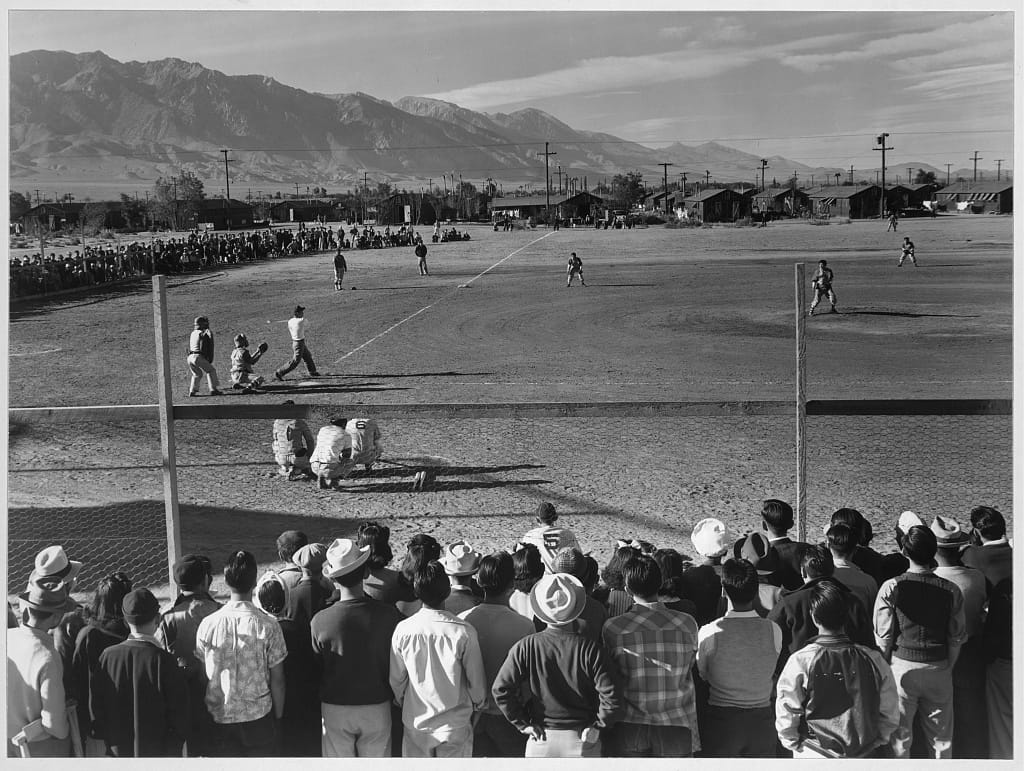

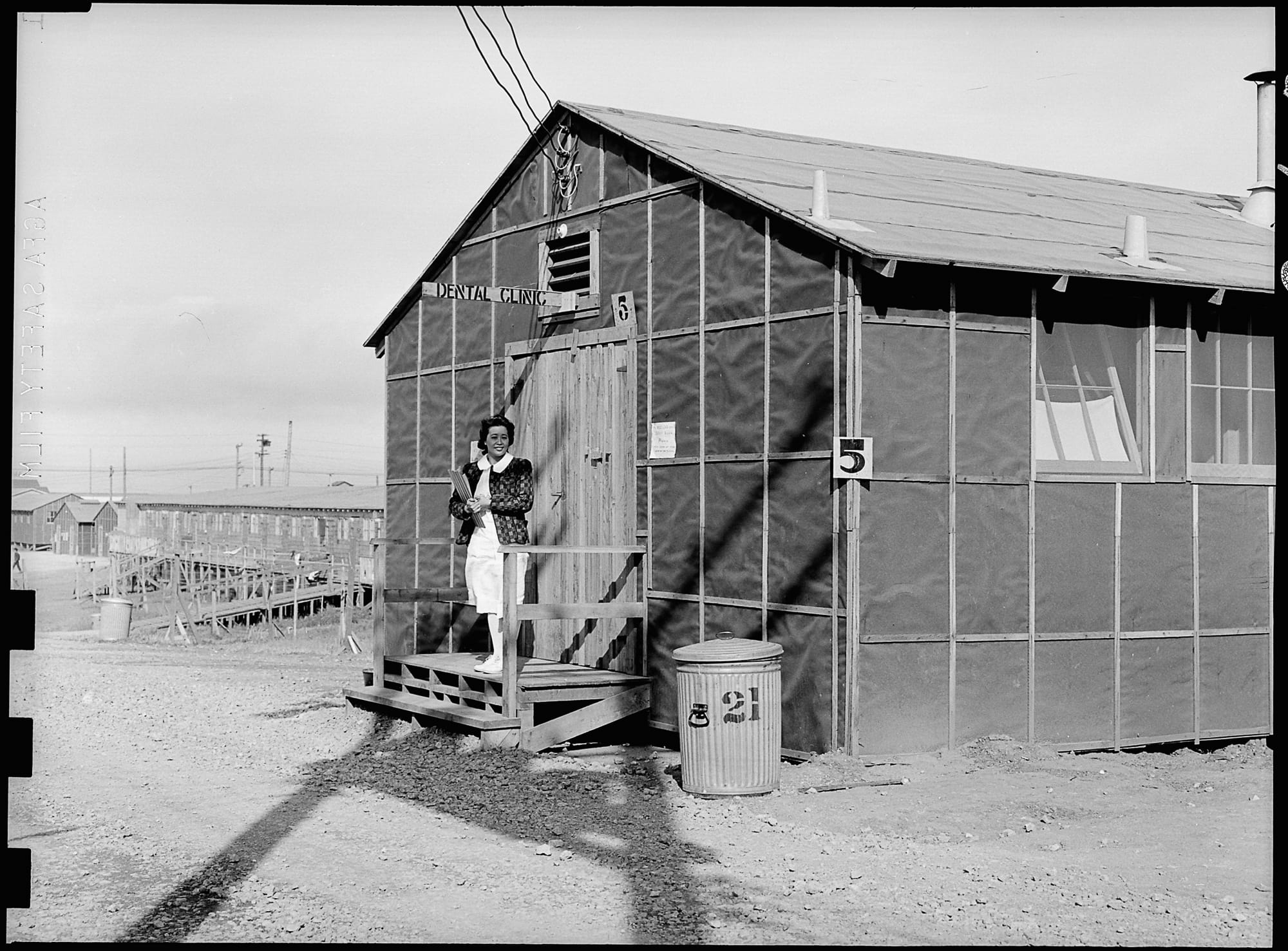

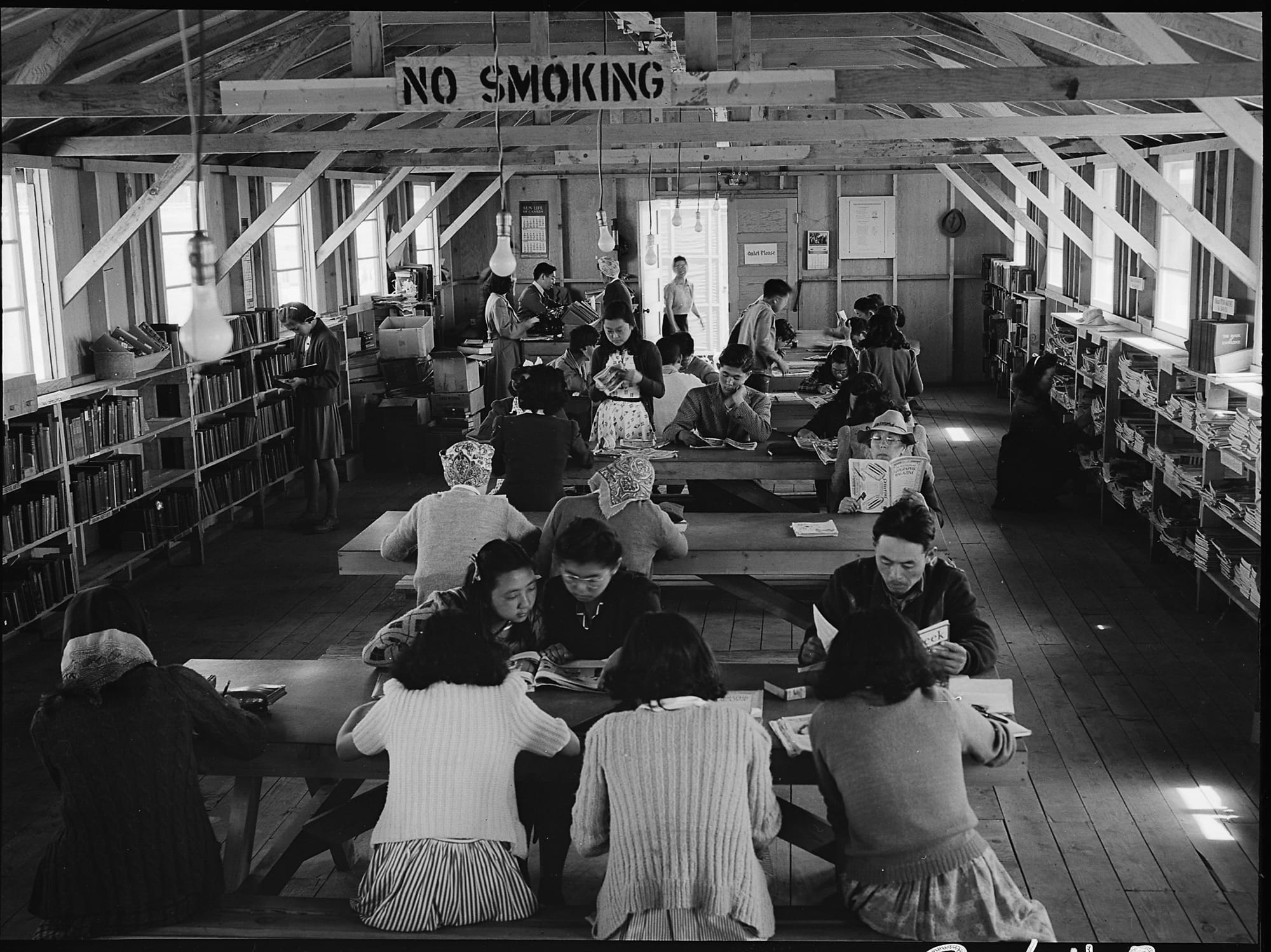

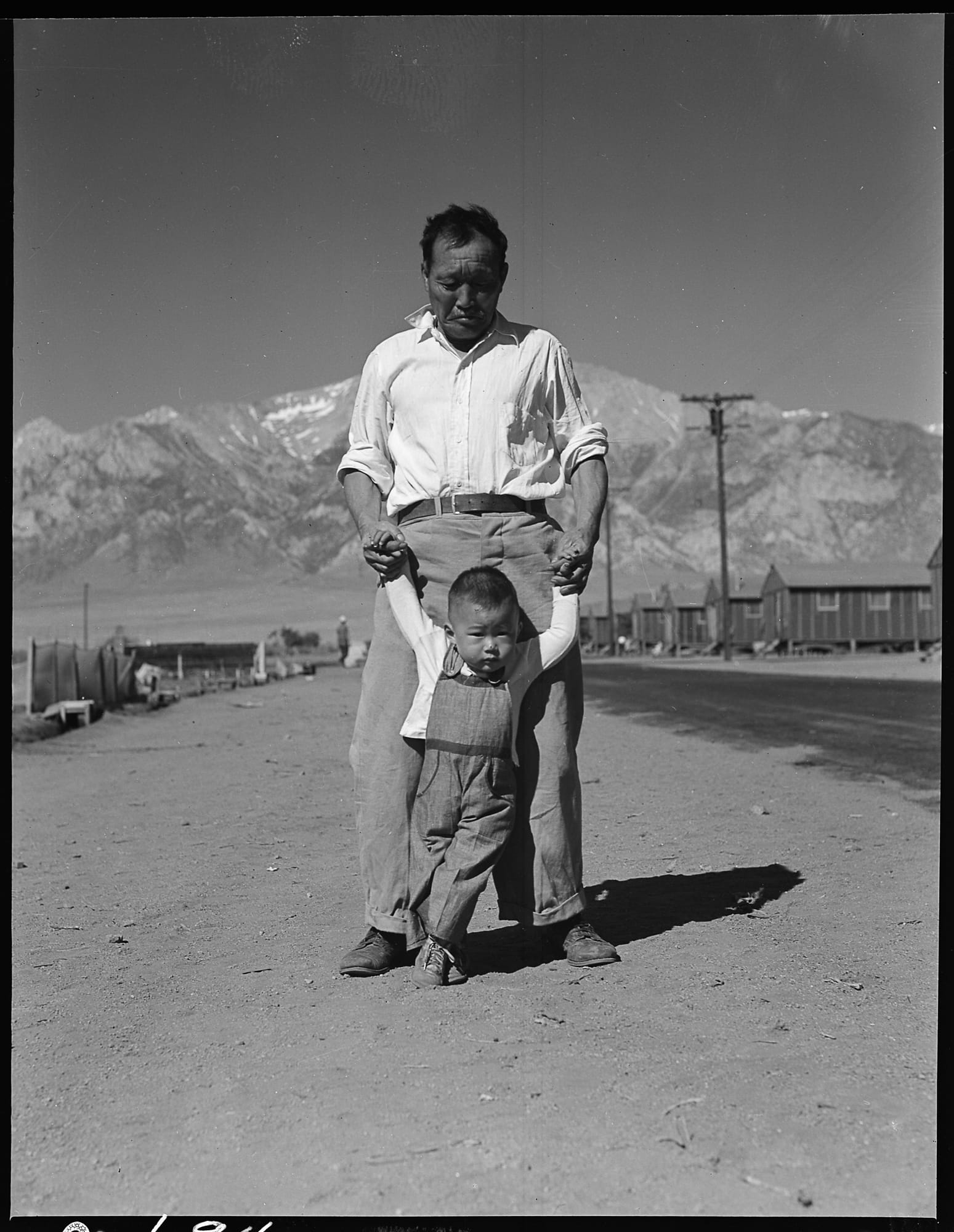

The collection includes more than 200 black-and-white photographs capturing daily life in the camp: smiling students in makeshift classrooms, workers performing routine jobs, and people playing baseball. Among them are beautifully composed portraits of detainees—intimate and dignified images of incarcerated men, women, and children.

Some of the portraits shot by Ansel Adams at the Manzanar War Relocation Center. Source: Library of Congress

Adams was compelled to photograph the camp and its residents after a longtime Japanese employee of his parents was arrested and sent to a camp in Missouri. The arrest angered Adams, who wrote about the collection:

“The purpose of my work was to show how these people, suffering under a great injustice, and loss of property, businesses and professions, had overcome the sense of defeat and dispair [sic] by building for themselves a vital community in an arid (but magnificent) environment....All in all, I think this Manzanar Collection is an important historical document, and I trust it can be put to good use."

Yet, despite Adams’ motivation for the series, looking at these photographs, which depict mostly smiling subjects, seemingly content – one might get the sense that the life in the camps wasn’t that bad.

Some of the scenes of life in the camp shot by Ansel Adams at the Manzanar War Relocation Center. Source: Library of Congress

But Adams’ lens captured only one side of the story.

Famed documentary photographer Dorothea Lange— best known for her Dust Bowl photographs — also documented the “evacuation” of Japanese Americans, but many of her photos told a much different story. Lange was hired by the War Relocation Authority (WRA) in 1942 to document the relocation of the detainees.

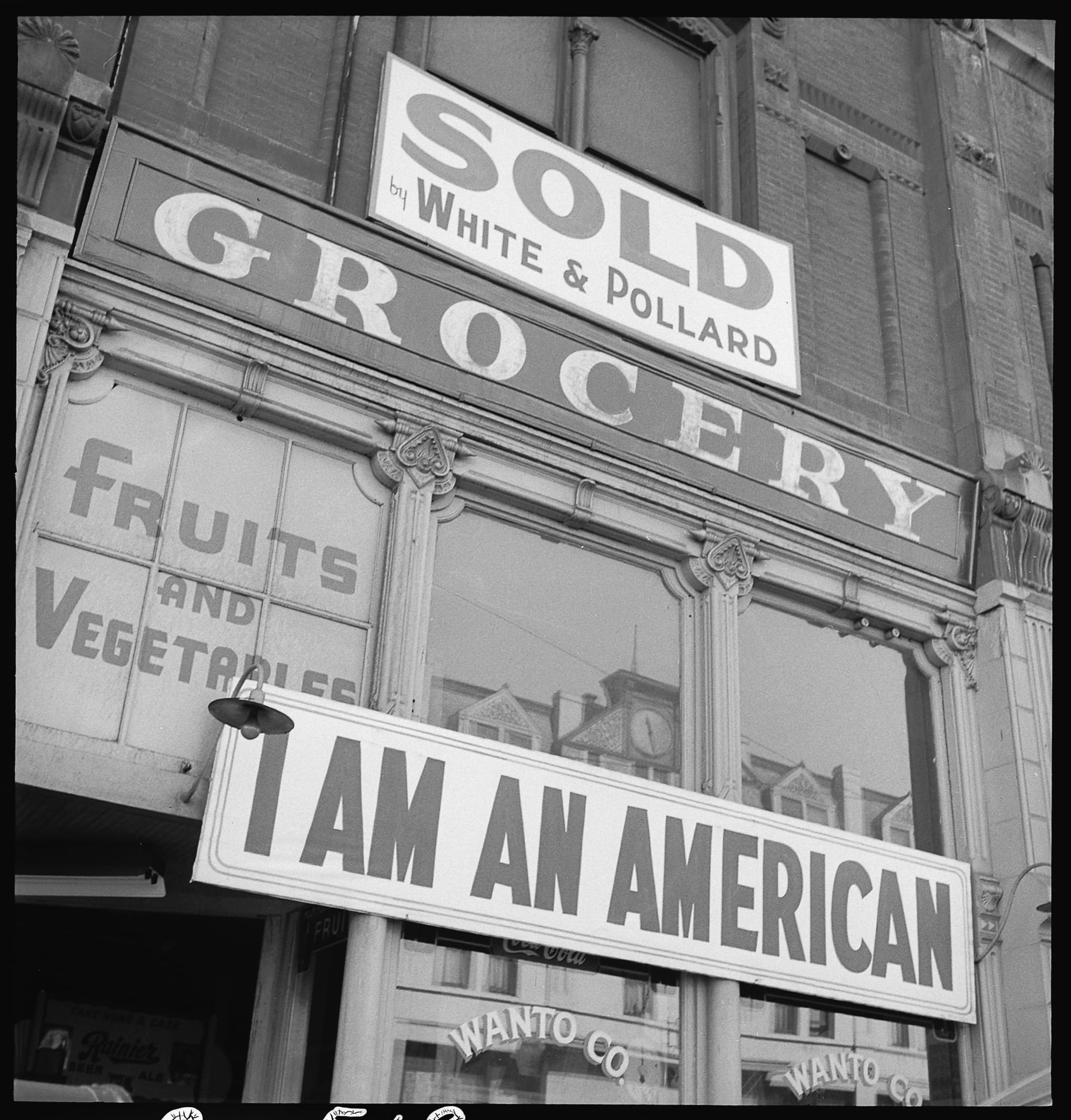

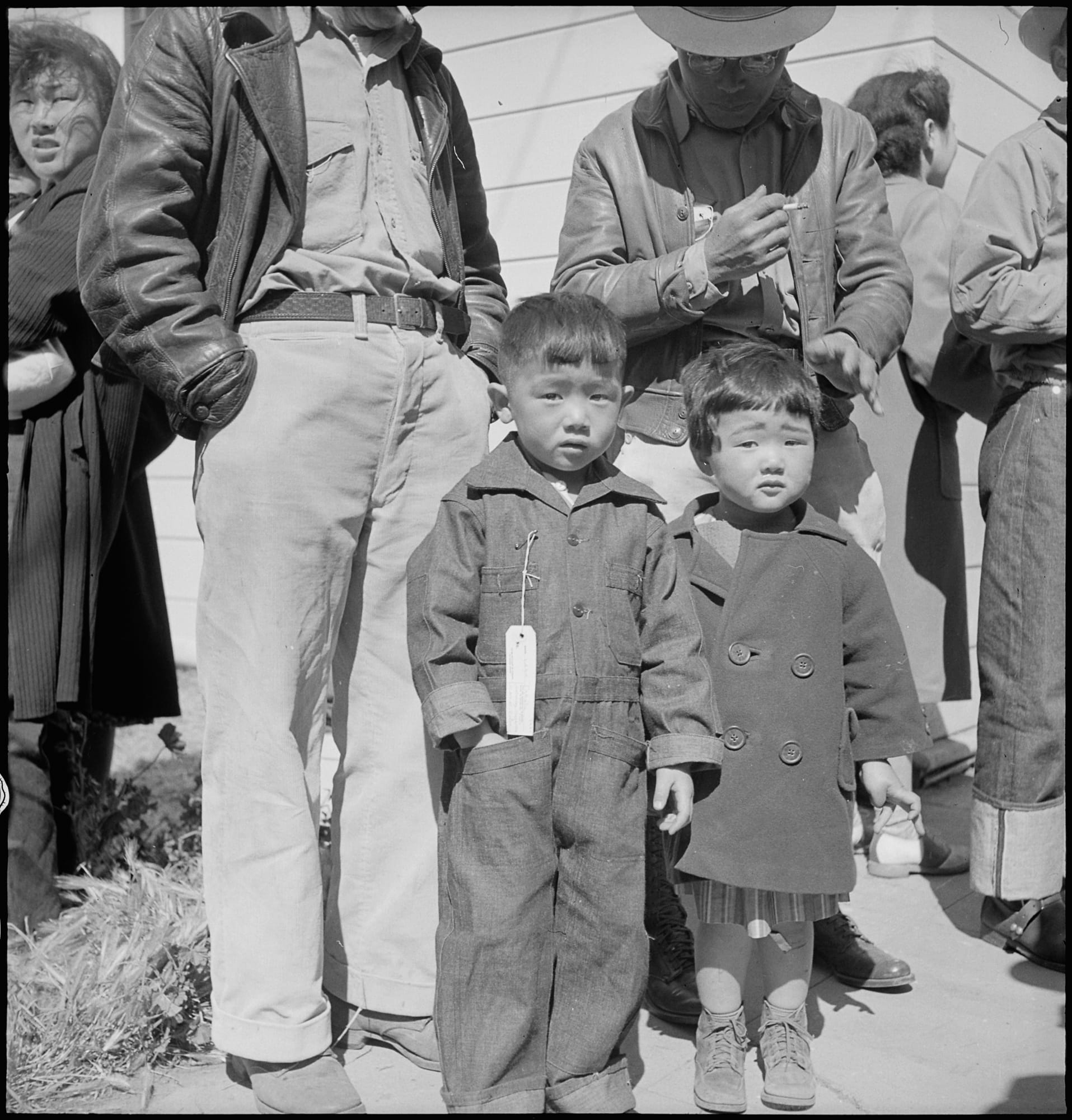

In Lange’s photos, you see families packing up their family’s belongings, children with identification tags hanging off their jackets, and Japanese American owned businesses having going-out-of-business sales. Lange’s photos depict groups of people huddled together after leaving their homes and businesses, as they face an uncertain future hundreds of miles from their homes in San Francisco’s Japantown and across California.

Photos by Dorothea Lange for the War Relocation Authority documenting the "evacuation" of Japanese Americans in California in 1942. Source: National Archives.

These haunting images are powerful and heartbreaking, and they did not send the message that the WRA wanted to deliver to the American people. Many of the photos were quietly withheld from the public. The National Archives has pushed back on claims that the photos were censored for decades, noting that they were available after the war.

In a post on the Nation Archives’ website, Nicholas Natanson, an archivist with the National Archives Still Picture Branch said:

“What is the case is that the bulk of Lange's WRA imagery was withheld from the public during World War II; that is, while the WRA was in operation, carrying out round-up, internment, resettlement activities that the Federal Government was obviously not anxious to publicize. However, this withholding ended after the war,” Natanson said.

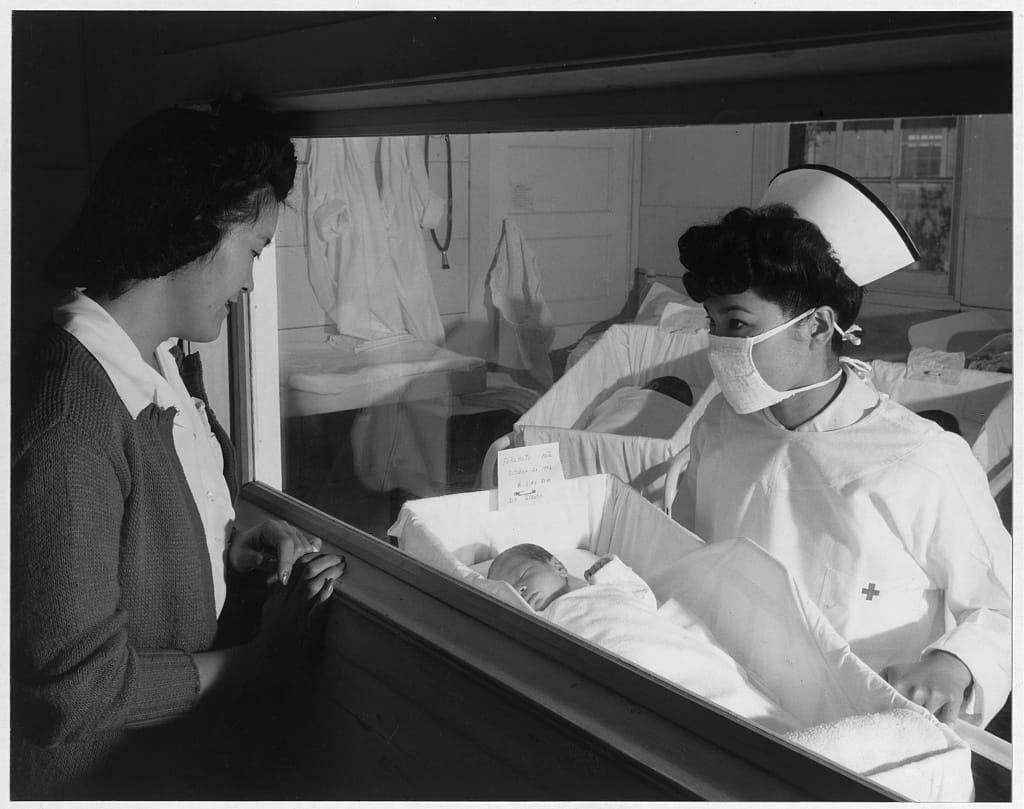

Photos by Dorothea Lange depicting life at Manzanar War Relocation Center in 1942. Source: National Archives.

The War Relocation Department worked hard to convince Americans that the Japanese were being protected and cared for in the internment camps. But the wounds of Pearl Harbor were still fresh. A WRA propaganda film titled "A Challenge to Democracy" delivers a message carefully crafted to address the widespread anger towards the Japanese, while also showing how humanely the families were being treated: These families are being treated well, but not too well. The narration reads:

"They are not prisoners. They are not internees. They are merely dislocated people. The unwounded casualties of war."

"Challenge to Democracy" propaganda film from the War Relocation Authority. Source: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/4966460

Blueprints, newspapers, databases

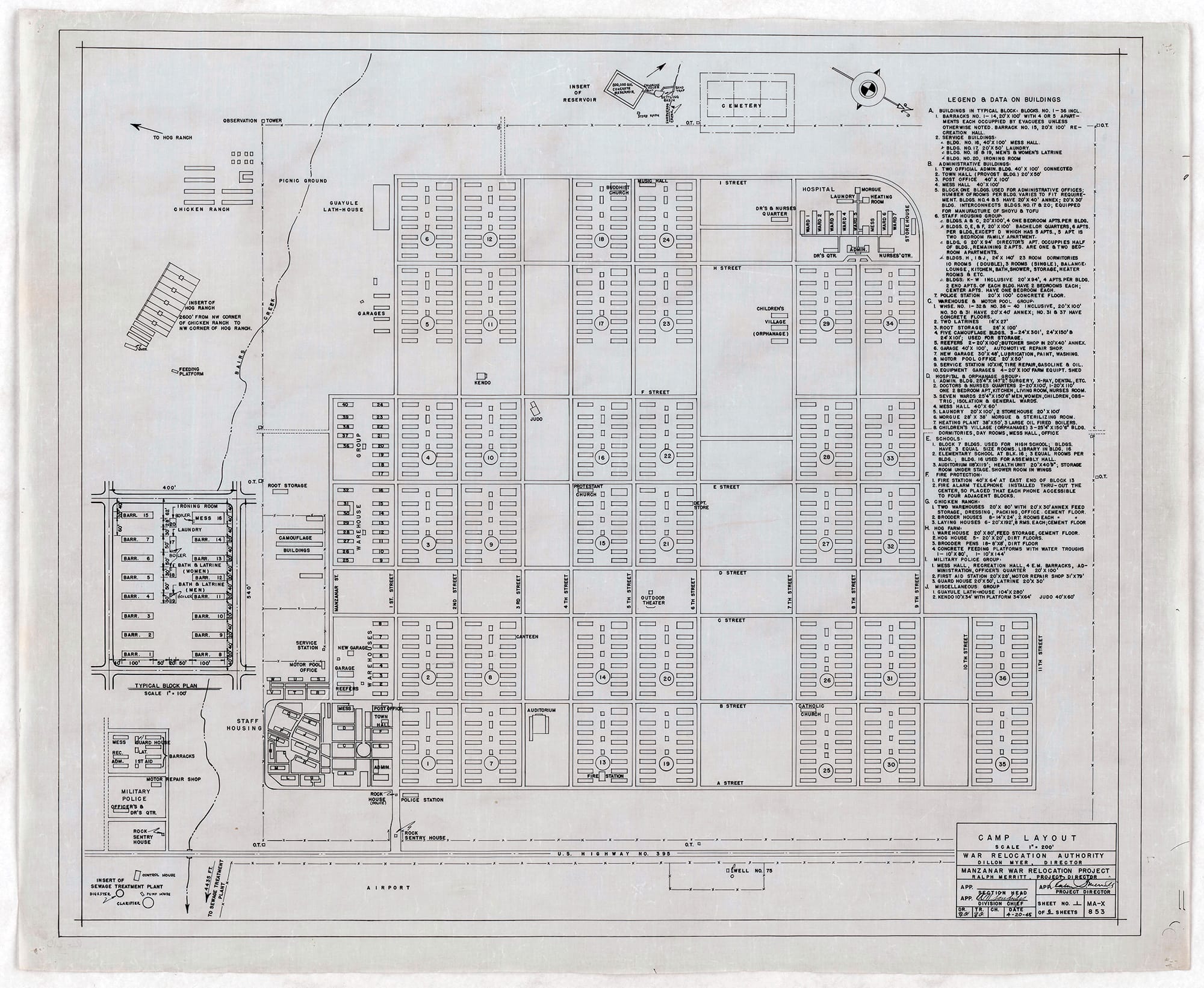

The National Archives has a rich assortment of records including films, audio, site plans, and other documents, in addition to the photographs.

Among the archives are the blueprints for each camp. Here's the plan for Manzanar War Relocation Center.

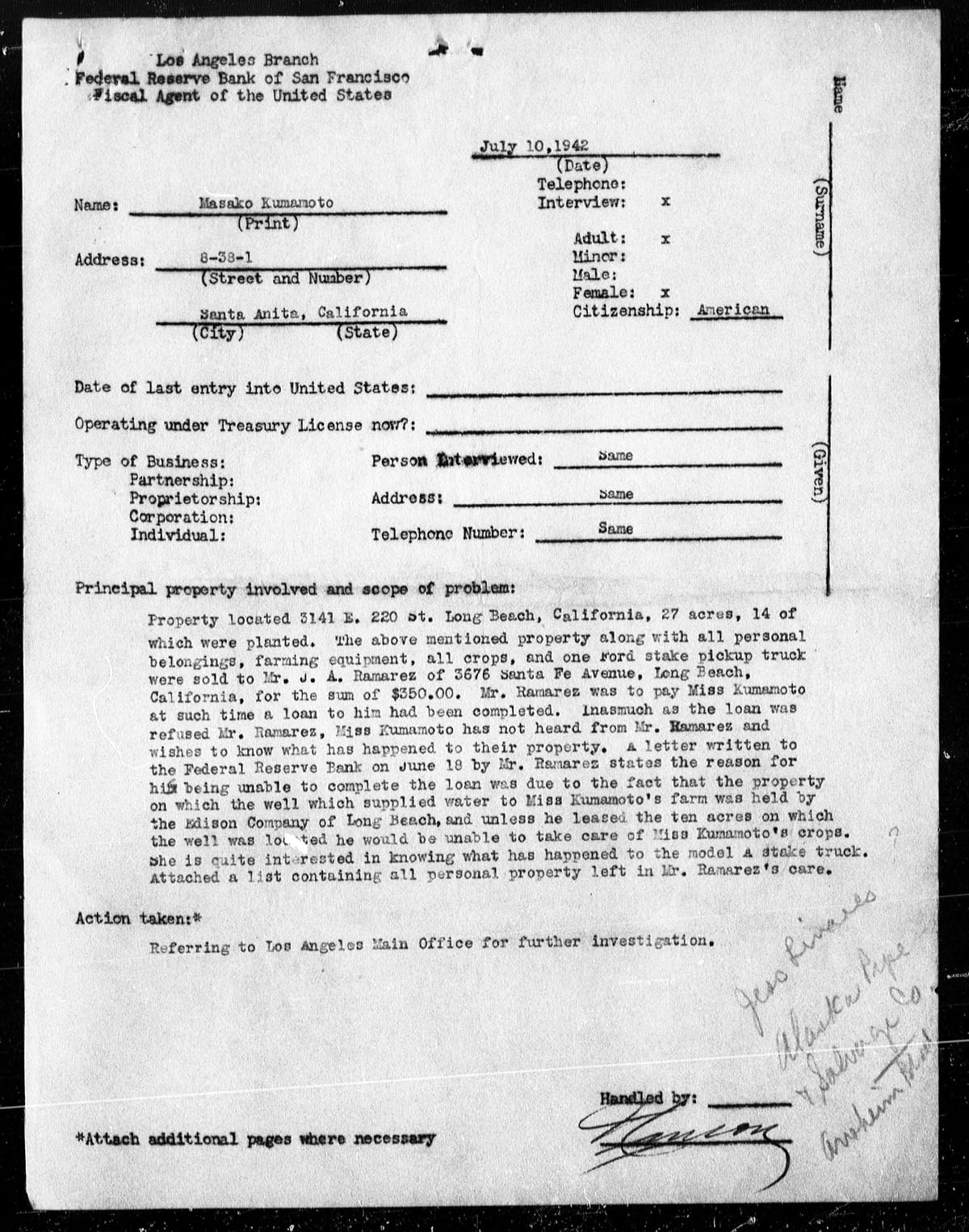

Some of the documents describe the desperate attempts to find out what has happened to the property and real estate that the detainees had to discharge before being forcibly relocated.

Here's one such document describing Masako Kumanoto's property and a dispute about their 27 acres of property and all of their belongings were sold to a neighbor for $350, but the detainee had not heard from the buyer, and was unsure about the status of the property.

Many of the camps had their own newspapers. Here's an edition of the Manzanar Free Press from Aug. 12, 1942.

Here's photo from one of the press rooms at the Heart Mountain, Wyoming camp.

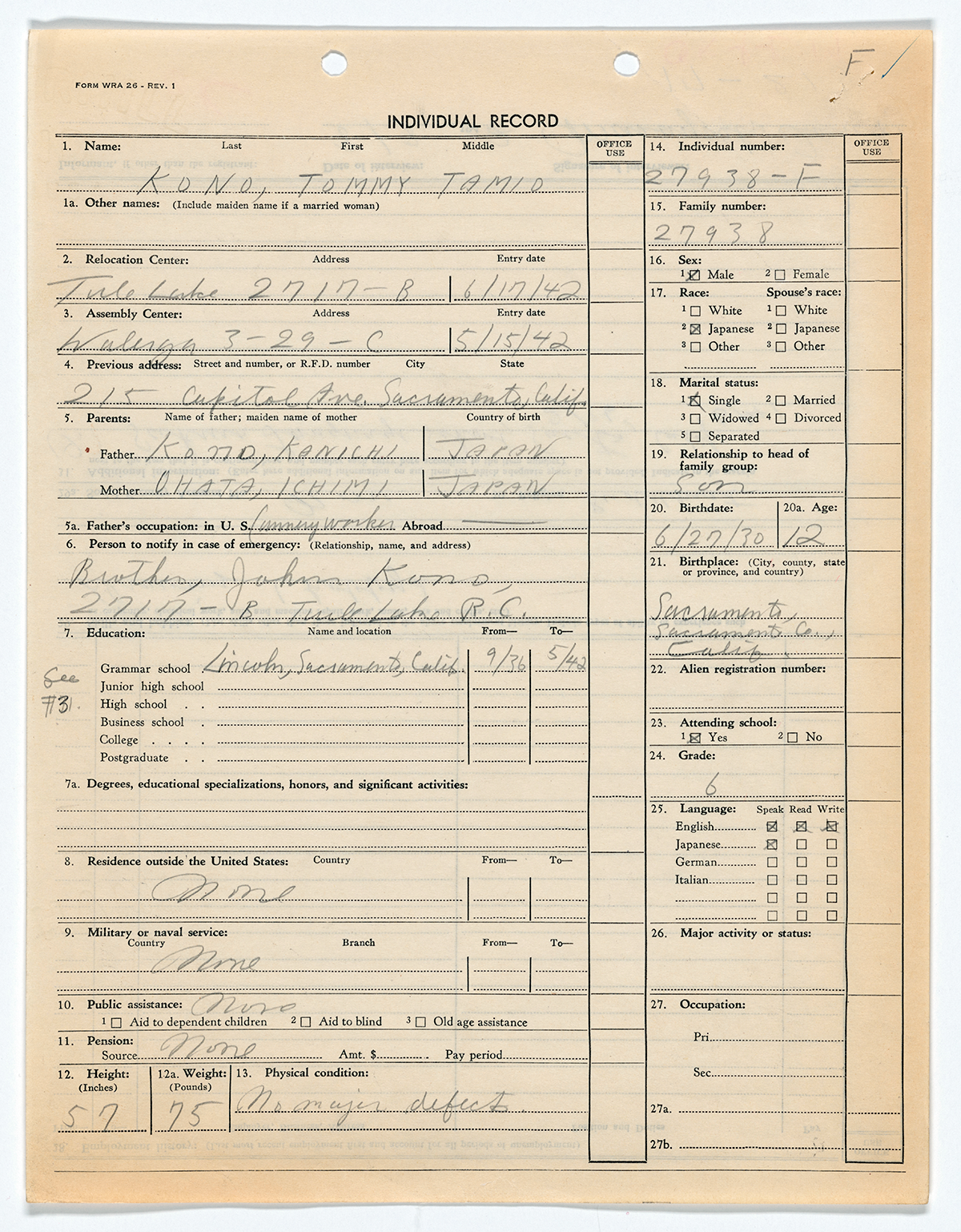

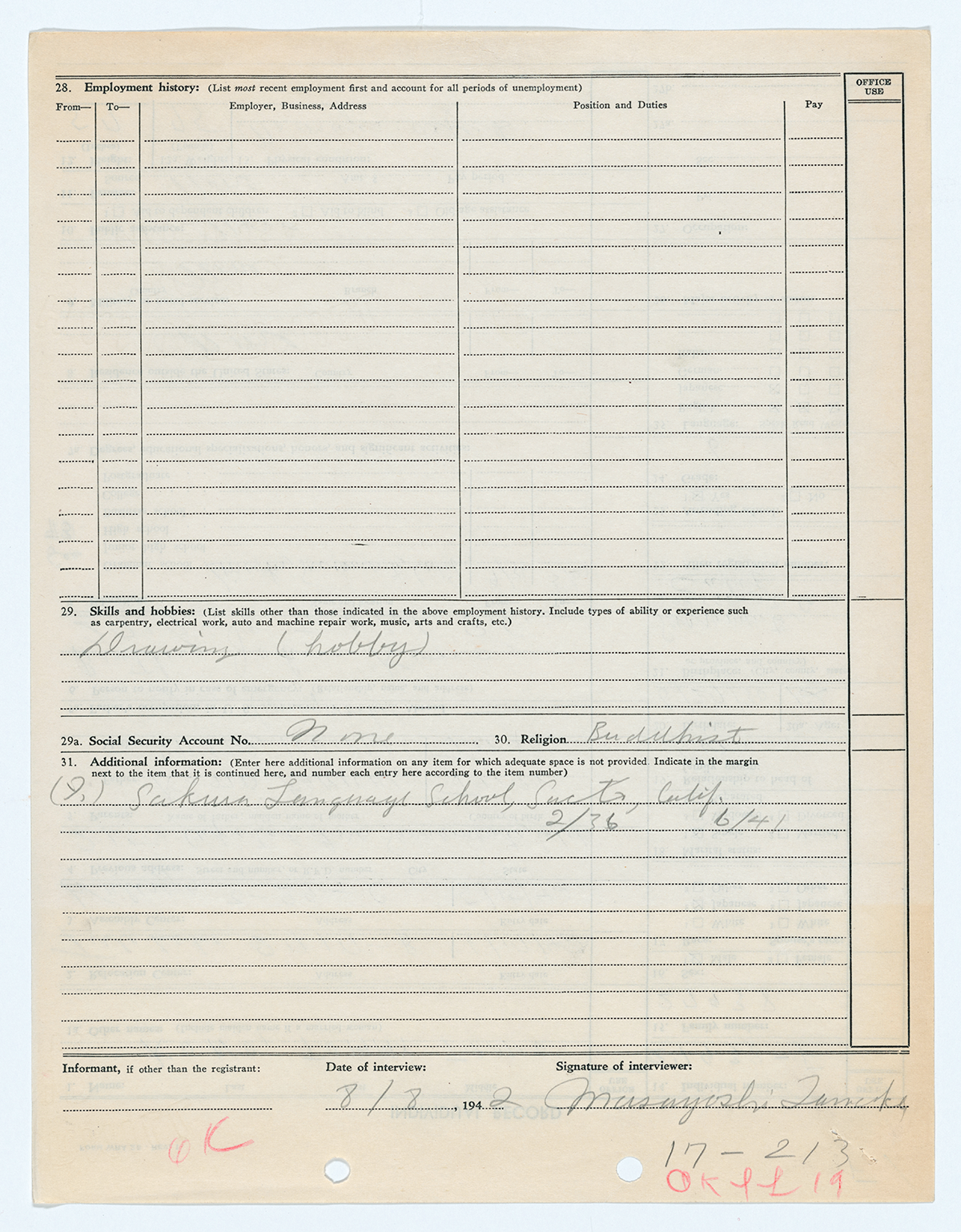

One particularly interesting file is a text file featuring detailed data on over 100,000 incarcerated people who were processed at intake using a detailed form. Form 26 asked about where the person was born, how long they attended school, religion, marital status, work skills, language ability, and much more. This data was hand-written on forms, using an incredibly complicated (but clever) set of codes to cram a huge amount of data into 80 characters per row. This data was recorded on magnetic tape and extracted as an ASCII text file in 2021.

Individual Form 26 Record for Tommy Tamio Kono. Source: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/259485500

Thankfully the good folks at the National Archive also preserved the old technical documentation for this dataset.

I took a stab at writing a script to extract this data so you can actually search and read through it. I can imagine this might be extremely helpful for someone researching their family history, so you can download the script and data here.

Reparations 45 years later

According to the National WWII Museum, detainees lost over $400 million worth of property during their incarceration. In 1948, Congress issued $38 million in reparations for lost assets, but calls for a formal apology and further restitution continued to grow.

Among those advocating for reparations was Japanese-American actor George Takei—who played Sulu on “Star Trek”— who was forced from his home and relocated with his family as a child.

Takei testified before the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians in California in 1981 advocating for reparations. Takei recalled:

“I was 5 years old at the time. It was a terrorizing morning I will never be able to forget. Literally at gunpoint, we were ordered out of our home."

Actor George Takei recalls his memories from his family's forced incarceration in WRA camps. Source: YouTube

Finally, in 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed a bill, which formally acknowledged:“the fundamental injustice of the evacuation, relocation, and internment of United States citizens and permanent resident aliens of Japanese ancestry during World War II.”

The law also formally apologized on behalf of the American people, and authorized payments of $20,000 to about 60,000 survivors.

At a ceremony signing the bill, Reagan said:

“No payment can make up for those lost years. So, what is most important in this bill has less to do with property than with honor. For here we admit a wrong; here we reaffirm our commitment as a nation to equal justice under the law.”

Even then, it would take another two years before the payments were finally issued.

You can subscribe to our newsletter to get future posts delivered to your inbox for free. 👉🏻 📫 Subscribe now.

Sharing is caring

📣 If you think your followers or friends may like it, please consider sharing it.

🙋🏻♀️ If you have any suggestions, comments or requests, please email them to beautifulpublicdata@gmail.com

Thanks for reading!

- Jon Keegan

Bluesky: @jonkeegan.com

Mastodon: mastodon.social/@jonkeegan

AIS Ship Movements Framed Prints

Ships at sea are constantly broadcasting their real-time location, identification, speed, and orientation data via AIS. Plotting out a years worth of ship movements (2023) reveals beautiful patterns of our journeys at sea. Ferries, fishing boats, cargo ships and sailboats' coordinates etch electric pathways in these stunning visualizations of NOAA data.

🚢 Adding new maps soon!