Trademark Design Codes

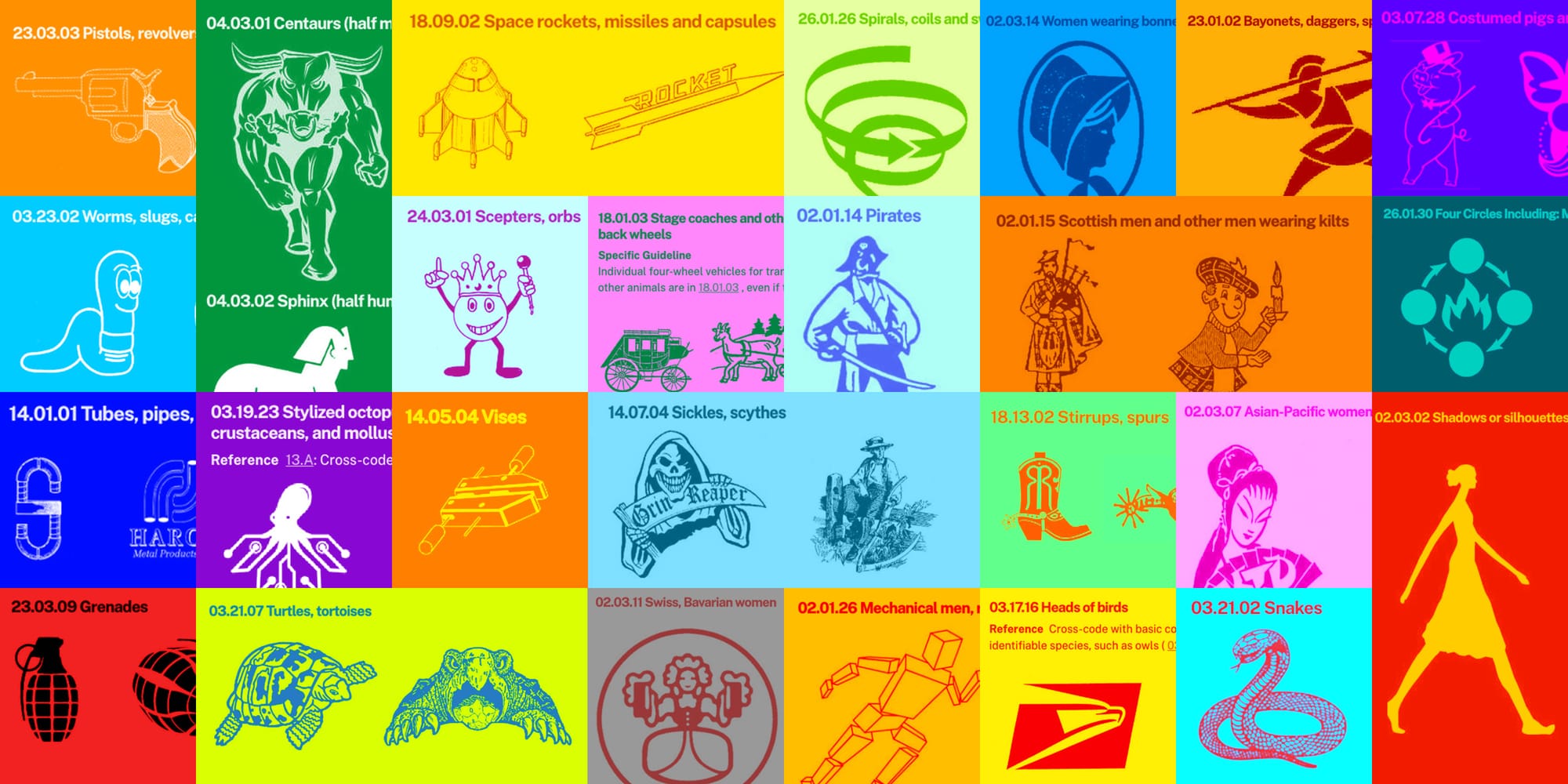

The United States Patent and Trademark Office has a system of 1,400 descriptive "design codes" allowing you to search for trademarks with “Rickshaws”, “Centaurs” or “Mechanical women”.

Editor's note: All trademarks, service marks, and logos appearing in this article are the property of their respective owners who own all rights in and to their trademarks and copyrights, and does not imply any affiliation with or endorsement by them.

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) maintains several massive public databases of registered trademarks, some of which go back to 1870. “Wordmarks” (think Coca-Cola, FedEx and Google) and graphic logos (Starbucks, Apple, Target) of brands large and small are all in there, as are the trademarks of millions of smaller businesses you’ve probably never heard of.

Trademarks are used to identify goods or services. A trademark protects a company or individual’s unique name or design that applies to a specific application. You can even trademark sounds or smells. But there are only so many names and designs you can come up with, so there is the possibility of consumer confusion. When a company or an individual wants to register a new trademark, the USPTO needs to review the application and then search this vast archive to make sure the applicant’s trademark doesn’t conflict with another trademark already in use.

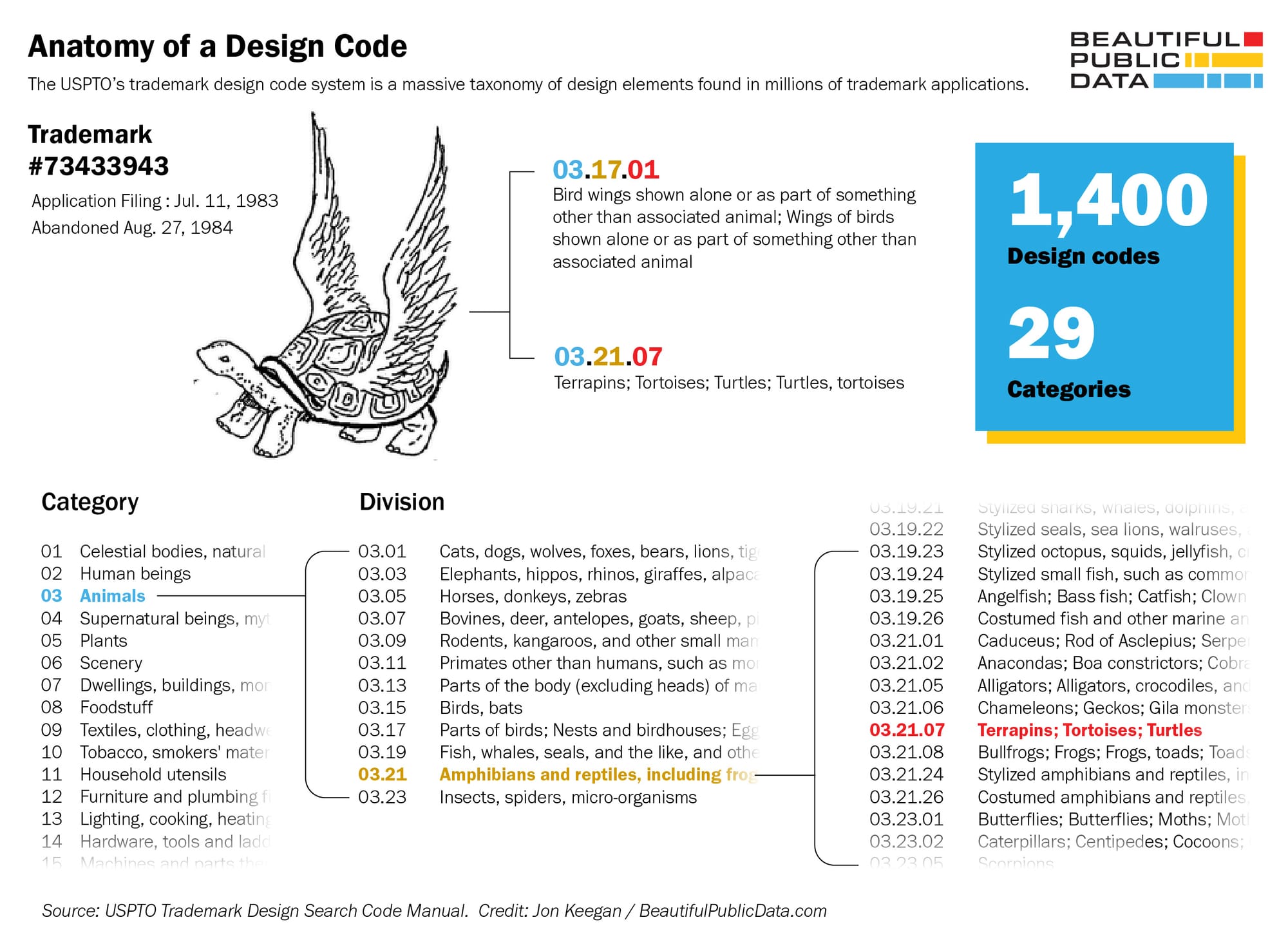

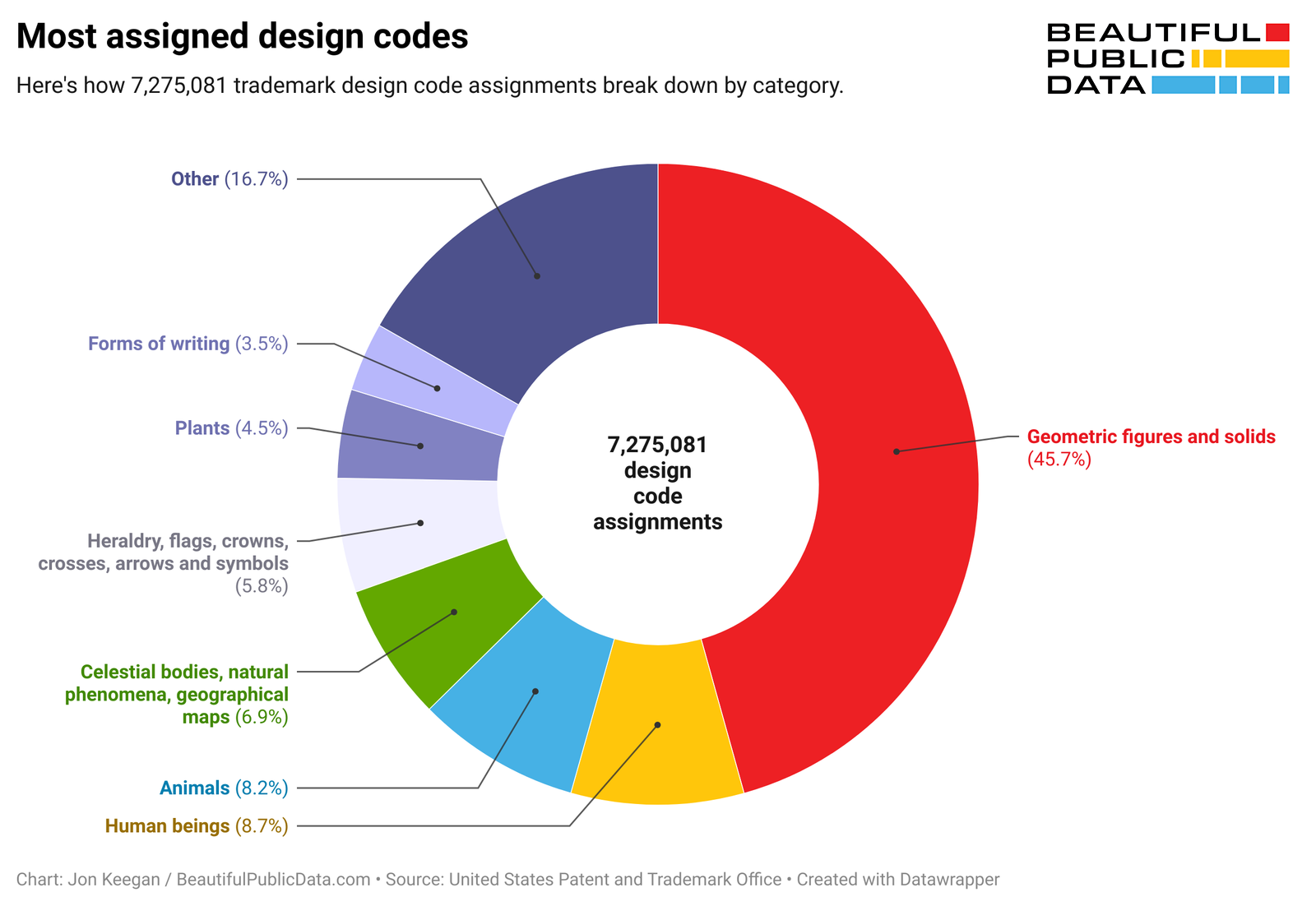

But how do you search for a swoosh, a mermaid wearing a crown or a cartoon tiger? To solve this problem, the UPSTO devised a system of 1,400 numeric “trademark design codes'' that describe each trademark. A trademark might have several of these codes representing different elements of the trademark. The numbering system is a clever hierarchical system to create a taxonomy for all the many weird things that might be in a logo.

Rickshaws, Centaurs and Mechanical Women

I downloaded some of the massive files from the USPTO’s research datasets of trademarks to explore how these design codes are used. These design codes cover an incredibly wide range of things, and many of them are delightful. You will find design codes for “Tri-cornered hats”, “Emus”, “Ball bearings”, “Rickshaws”, “Centaurs”, “Mechanical women”, “Scottish men and other men wearing kilts” and “Winged human heads, feet, shoes or other parts”.

Let’s look at one example of a design code. Code number 03.21.07 is used for “Terrapins; Tortoises; Turtles; Turtles, tortoises". In this case, the first two digits represent the category of “Animals”. The second pair of digits represents division 21 in that category which is “Amphibians and reptiles, including frogs, snakes, lizards, and turtles”. The last two digits “07” is for “Terrapins, Turtles, Tortoises”.

For example this trademark featured an illustration of a tortoise with wings, so in addition to “Turtles; Terrapins; Tortoises” it also was tagged with 03.17.01 - “Wings of birds, shown alone or as part of something other than associated animal; Bird wings shown alone or as part of something other than associated animal”.

But the taxonomy of trademarks is a different beast than the taxonomy of animals we are familiar with, and things quickly get weird. In addition to that turtle code, there’s also:

- 03.21.24: “Stylized amphibians and reptiles, including frogs, snakes, lizards, and turtles” and

- 03.21.26: “Costumed amphibians and reptiles, including frogs, snakes, lizards, and turtles, and those with human attributes”.

These codes are chosen and applied manually by the USPTO staff reviewing trademark applications. And because there are often many different elements of a trademark, several different codes may be needed to correctly classify the contents of the trademark.

Applicants get to review the design codes assigned to their application and revise them if necessary. “We've assigned these design codes to your trademark and the applicants themselves will have an opportunity to say, well, actually, it's not an elf, it's a troll or whatever it is. So could you please code that appropriately?” explained Jason Lott, Managing Attorney for Trademarks Customer Outreach at the USPTO in an interview with Beautiful Public Data.

Popular Pairs 👯♀️

The most frequently used design codes are just descriptions of shapes. For example the most often used design code is pretty broad: 26.01.21: “Circles that are totally or partially shaded” which was applied to 280,356 trademarks in the files I analyzed.

The least used code I found is much more specific: 11.05.07: "Can openers (electric); Can openers, electric; Electric can openers; Openers, can, electric" which was applied to three trademarks.

The average number of design codes applied to a trademark is about 3, but one exceptionally busy trademark has 105 design codes, and when you see the image you understand why.

Browsing the collection of trademarks through pairs of design codes is a particularly interesting way to explore this dataset. When it comes to logos of American companies, certain pairs of design elements appear together frequently. There’s plenty of EAGLES and SHIELDS, AMERICAN FLAGS and RIFLES, and DOGS with SUNGLASSES. There are also quite a few AMERICAN INDIANS with ARCHERY BOWS and PIGS with CHEF’S HATS. (If these links don't work, view this story in your browser)

I built an interactive widget to let you explore some of the more whimsical pairings of design codes. 👇🏻

From Paper to Databases

The current system was put in place decades ago, but has evolved over time.

"The design code system that we have right now really started to come about in the 1980’s when they started to transition away from paper. Back at that time when you were going through a paper stack, they would be sorted appropriately according to design, sometimes by registration number," explained Lott. As the images in trademarks began to contain more elements, this system was not up to the task. "What if you have something that has a tree and it has an elf? What would you do with that?" said Lott.

Browsing through some of the design codes, I was struck by how some of them sounded…a little old. For example there are references to “frankfurter sandwiches”, “typewriter ribbons”, "hobos" and “dunce caps”. Likewise it would be hard to imagine any trademark in 2024 including “washboards”, “inkwells”, “soup tureens”, “flash bulbs”,“telephone booths”, “adding machines”, or “pocket watches.”

Lott explained that sometimes a company's trademarked logo was created in another era. “We have trademarks that are well over 100 years old” and that sometimes these old sounding codes are still relevant. “You're still gonna be using some of those terms because it might be that there's a Bavarian woman [in the trademark].”

When it comes to updates of the design code system, USPTO spokesperson Christina Whitaker told me in an email that the USPTO will “continue to make revisions, as well as work to make the ability to update the systems more streamlined.” Whitaker said that changes to the design codes system are made by “a standing committee composed of supervisory attorneys” and that suggested additions or revisions come from two sources. “First, applicants and other external stakeholders ask questions or propose changes from time to time, and may be considered the first line reflecting evolving trends in the marketplace. Second, Trademarks has a large corps of examining attorneys as well as paralegal specialists who use the design code system on a daily basis.”

Changes to reflect changing technology are considered as well. “Additions are most needed as new products emerge and establish ubiquity: toy drones and tablet computers jump to mind, for example,” said Whitaker.

In addition to adding or removing items from the code system, sometimes broad categories are broken down to provide more specificity. Whitaker explained, “We recently revised some codes of animal designs to create separate groups for felines, canines, equines, and bovines, where these had in some codes been previously grouped together”.

A Perfect Use Case for AI?

Thinking about this problem of describing an image with words immediately made me think that the new wave of AI tools might be a perfect use case for this system. When I asked Lott about the potential of AI being used to automatically describe trademarks, he was cautious in his response. Lott said “I can neither confirm nor deny any upgrades to our trademark search system. However, that sounds like a really great use of technology.”

Sharing is caring 📣 If you think your followers or friends may like it, please consider sharing it.🙋🏻♀️ If you have any suggestions, comments or requests, please email them to beautifulpublicdata@gmail.com Thanks for reading!- Jon Keegan (threads.net/@jonkeeganstories)